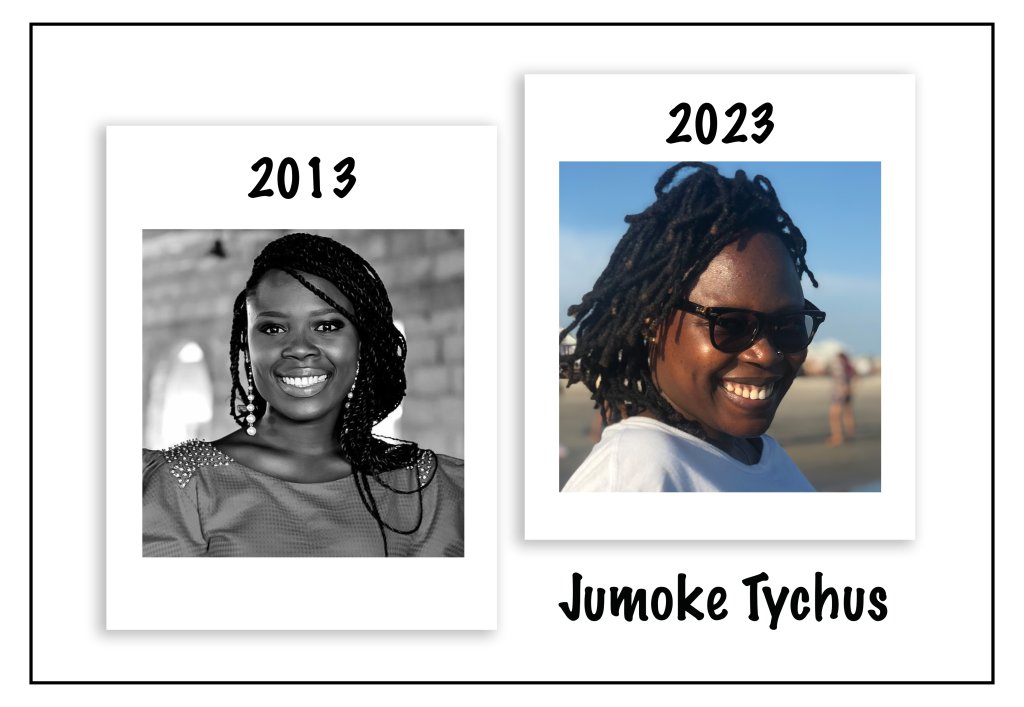

This is what Jumoke Tychus, a creative entrepreneur, thinks of Section 297 of the Nigerian constitution which only permits abortion if done in “good faith” to preserve the mother’s life, after considering her state. She is a mother of two and has taken a break from caring for her newborn to talk to me about motherhood.

Being pro-choice, her decision to become a mother was deliberate, informed by her own introspection on trauma she had experienced and how she wanted to avoid repetition, saying, “If I had to do motherhood, I want to do it right.”

For her, there is the “need to be sure you’re ready physically, spiritually, mentally, and psychologically. I don’t think a law can determine that for me.”

As a student of Philosophy at the university in 2009, I argued pro-life in an Applied Ethics class on abortions through the lens of my religious and societal bias. I had grown up associating abortions with taboos, and a culture that silences the exercise of agency in shame. 14 years later, I realised that the concept of choice was alien to me in that class, and I had never really thought of my agency. As a student of life, I argue for agency and free will.

In the recent general elections, female voters accounted for about 47.5% of the total registered voters. Yet, there’s a profound dearth of female representation in the state of affairs, a gap that is visible in the laws and policies that affect women in the country. So laws like the archaic law on abortion persist because half of the population is not represented in the institutions that work to create and enforce legislation that informs every aspect of the lives of Nigeria’s nearly 100 million women.

But it is not all bad. If you looked at those statistics alone, you would never guess that there has been a conscious progression of women in Nigeria toward liberation from systemic oppression and deliberate erasure. This consciousness is igniting a sense of agency and imbuing them with the courage to rewrite their stories.

Time capsule image credit. Lex Ash (2013)

‘Dirty Laundry’, the recent mixed-media exhibition by writer and performer Wana Udobang, challenges society’s patriarchal and restrictive prescription for women. The travelling exhibition documents multi-generational stories of trauma and violence against women, weaving them into poems that console, inspire and admonish women, encouraging them to liberate themselves and seek their happiness.

For Wana, there’s a need to reimagine the issues of shame and violence in the systemic erasure of women in Nigeria.

“What was interesting to me is how people see themselves in all the stories and all the poems. For me, imagination is also a part of this liberation process.”

Wana talks about this re-imagination as allowing women to decide who they want to be, and how they want to exist in a world, knowing that there’s no one way to live.

Time capsule image credit. Aishat Augie (2012)

“It is so important because we live in communities and societies that are very prescriptive for women.”

The effects of living in such a society are harmful cultural laws, societal bias, economic limitations, and social expression. Statistically, nearly 3 in 10 women in Nigeria experience physical violence by age 15, and at least 2 million Nigerian girls experience sexual abuse annually with about 28% of rape cases reported. Practices such as child marriage are commonplace with 43% of girls married before the age of 18.

“A lot of people don’t even understand the impact of violence, physical violence, emotional violence, generational violence on the lives and bodies of women and girls.”

Liberation is our collective goal, but we cannot reach this place at the same time or through the same routes. The intersections a woman has in her identity, the more difficult it is to achieve full liberation. Most women who are part of disadvantaged minority groups, such as gender, disability, education, wealth and privilege, find themselves having to erase parts of themselves to find acceptance within the larger movement.

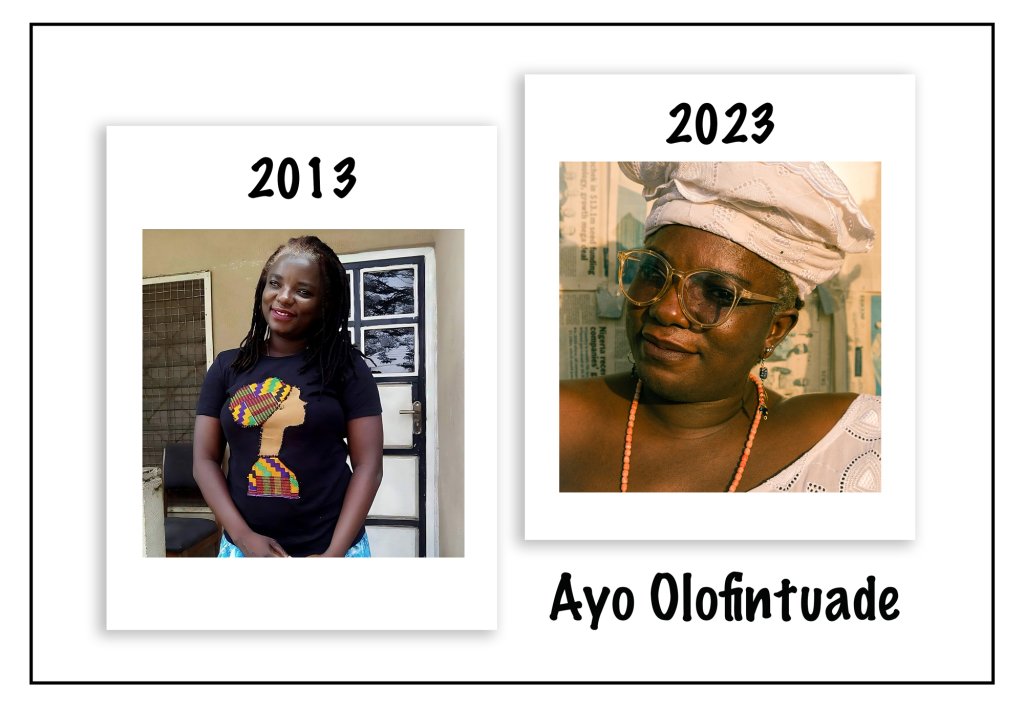

Women who identify as women in Nigeria have had their identity buried,” says writer Ayodele Olofintuade.

Being queer, Ayodele has had to battle against a society that does not recognise their choices.

“When I came out in 2014, I did not think about the big and little things like how my mom feels, and how my children will feel,” they say. “All I was thinking was, I will choke to death if I don’t come out of this closet.”

Time capsule image credit. Eniola Teslim (2023)

Ayo is proud of their heritage and well versed in its intricacies. This understanding of their cultural history and specifically the fact that they are preceded by generations of women who were fluid in their expressions, affirms their own identity. They speak about their indigenous communities and their support in the liberation of women.

“I see how women take their power back in Isese circles and how they take control of their lives. A lot of the women that openly practise are very fluid in their expressions, and how they see life.”

Ayo talks about the concept of “Ori,” (individual spiritual consciousness) in Yoruba mythology and how they believe it is the spiritual path the Nigerian woman is on.

“Your purpose is to reach the highest that head can become, they call it Iporin. And that is what Nigerian women of now are doing. They are reaching out for their core, they’re reaching out for their head, for that thing that makes them individuals.”

The Nigerian woman is reaching out for her individuality and has inspired the conscious progression towards liberation. We are documenting our re-imagination, as the past 10 years have produced more women-focused media platforms countering the historic bias of women in the media.

We are reimagining our stories.

Nigeria has always had women with a voice and choice, and I’ve witnessed her in ladies like the Feminist Coalition, a pivotal organisation during the #EndSars nationwide, artists like Tems who are making music history, and disruptors of political shackles like Senator Ireti Kingibe.

This liberation is as much an individual story, as it is our collective story.

Written by Chidera Muoka,

Editor-In-Chief,

Marie Claire Nigeria

Chidera Muoka has worked as a creative director and journalist for a range of media platforms. She has created, directed and produced integrated media campaigns for traditional and digital marketing strategies for clients in the culture, lifestyle and media industries.

She specialises in investigating and platforming a broad spectrum of stories that affect people and has directed and produced stories on gender-based violence and the rights of sex workers in Nigeria.